Between Print and Electronics, Art and Research

“Research” and “publishing” have always been closely related but are currently undergoing changes. Informed by technological and cultural developments, their practices and definitions are being debated. For new forms of interdisciplinary and artistic research, there is a corresponding need for new forms of publishing that go beyond the traditional academic textbook. WdKA Hybrid Publishing, a cross-departmental lab for art and design research publications at Willem de Kooning Academy, develops new, experimental forms of artistic research publications for print and digital media. The plan is to extend hybrid publishing to the multidisciplinary research practice at the Rotterdam Arts and Sciences Lab.

Hybridity of art and research

What is the future of publishing in a time when the digital revolution has happened and print is not going away? At a conference organized by Willem de Kooning Academy (WdKA) in 2009 called print/pixel, this very future of publishing was addressed by those interested in its stakes. Artists, designers, software developers, small and large book and newspaper publishers, and media researchers from the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Italy and the United States presented new approaches to design and publishing in a hybrid digital and analog world where, among others, print-on-demand and e-books were new technologies. Examples included books and magazines published in real time, generated from blogs, whose designs were automatically generated from databases and were authored using Open Source forms of collaborative writing and design. It became immediately clear that the future of publishing was not simply an issue of remediating traditional formats to new technologies but of inventing new publication forms.

Alessandro Ludovico, editor and publisher of the Italian new media arts magazine Neural, had been a fellow in WdKA’s research program at the time of the conference; and his research resulted in a book, Post-Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1984, which WdKA published in collaboration with the contemporary art space and book publisher Onomatopee in 2012. (Shortly afterwards, it appeared in French, Italian and Korean translations. It has its own Wikipedia article and its third edition is currently being printed.) Arguing that the death of print through electronic media had been predicted for almost an entire century, yet had never happened, Ludovico (2012) ultimately described a landscape of “post-digital” editorial art and design that hybridizes digital and print. Fast forwarding to 2018, hybrid media and experimental visual publishing has had little impact on the mainstream publishing industry but thrives in research-oriented art and design.[ref]For examples, see Silvio Lorusso’s ‘Post-Digital Publishing Archive’ (http://p-dpa.net) and the inventory of any contemporary artists’ book store such as PrintRoom in Rotterdam and San Serriffe in Amsterdam.[/ref] In academic artistic research, however, the PhD thesis and the journal article still prevail as publication formats, cautiously updated to accommodate visual work next to the written text.[ref]For an example, see the Journal of Artistic Research (https://jar-online.net).[/ref]

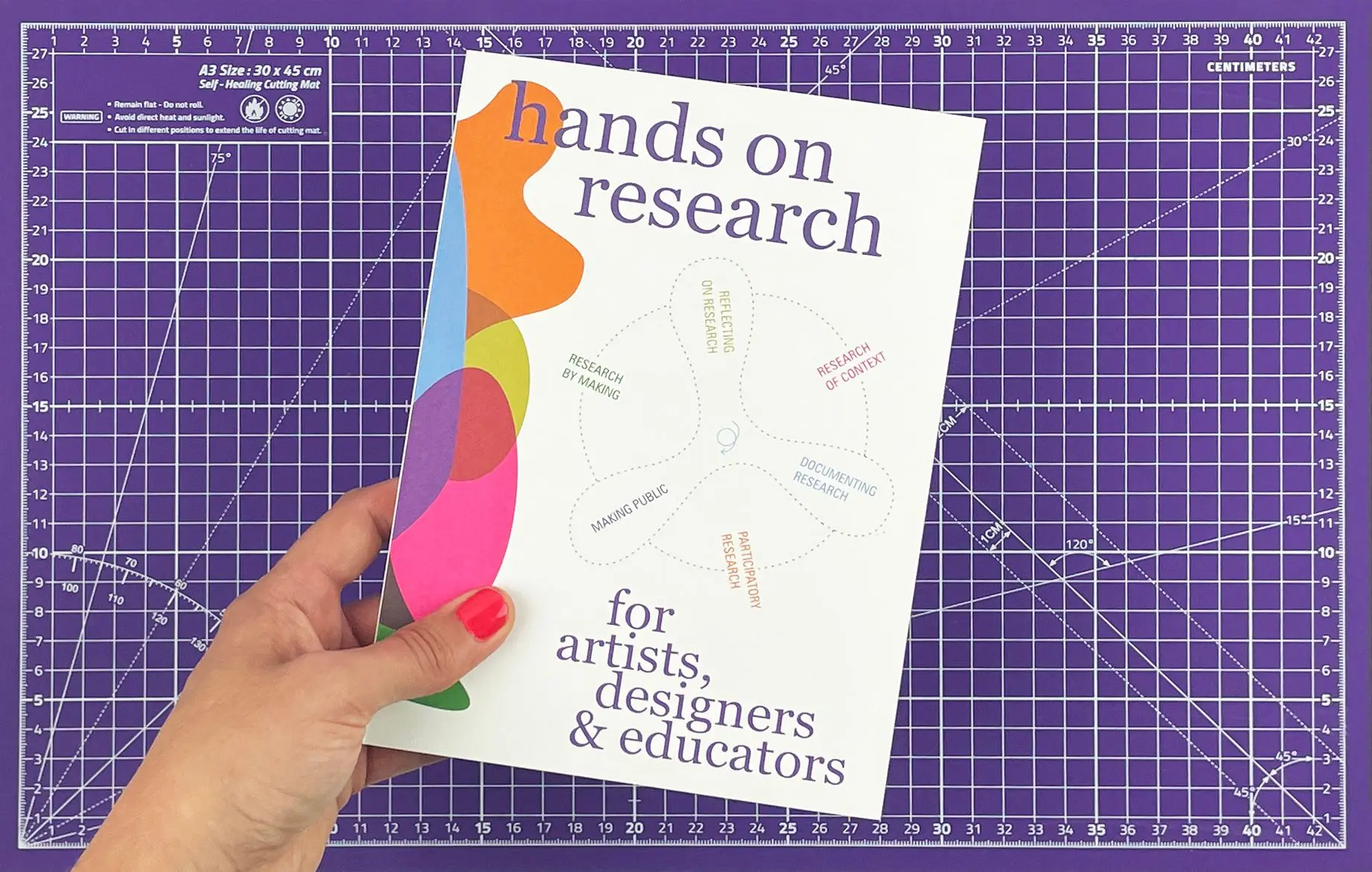

After completing A Hybrid Publishing Toolkit for the Arts in 2014—the result of a two-year joint research project with the Institute of Network Cultures at Hogeschool van Amsterdam—WdKA teachers and researchers (Kimmy Spreeuwenberg, Silvio Lorusso, Amy Wu, André Castro, Loes Sikkes, Renée Turner, Aldje van Meer, Roger Teeuwen and myself) founded WdKA Hybrid Publishing, a lab and think-tank to research and experiment with combined print and digital forms of publishing. Serving the school’s design curriculum as well as the development of its artistic and interdisciplinary research practice, WdKA Hybrid Publishing defines itself as a “platform for publishing research, while simultaneously conducting research through making, prototyping and incorporating iterative design processes” (Willem de Kooning Academy, 2018, “Hybrid Publishing,” para. 3). If one reads this statement carefully, then “publishing research” can both mean to publish research and to practice publishing as research. This ambiguity describes the work of the lab very well.

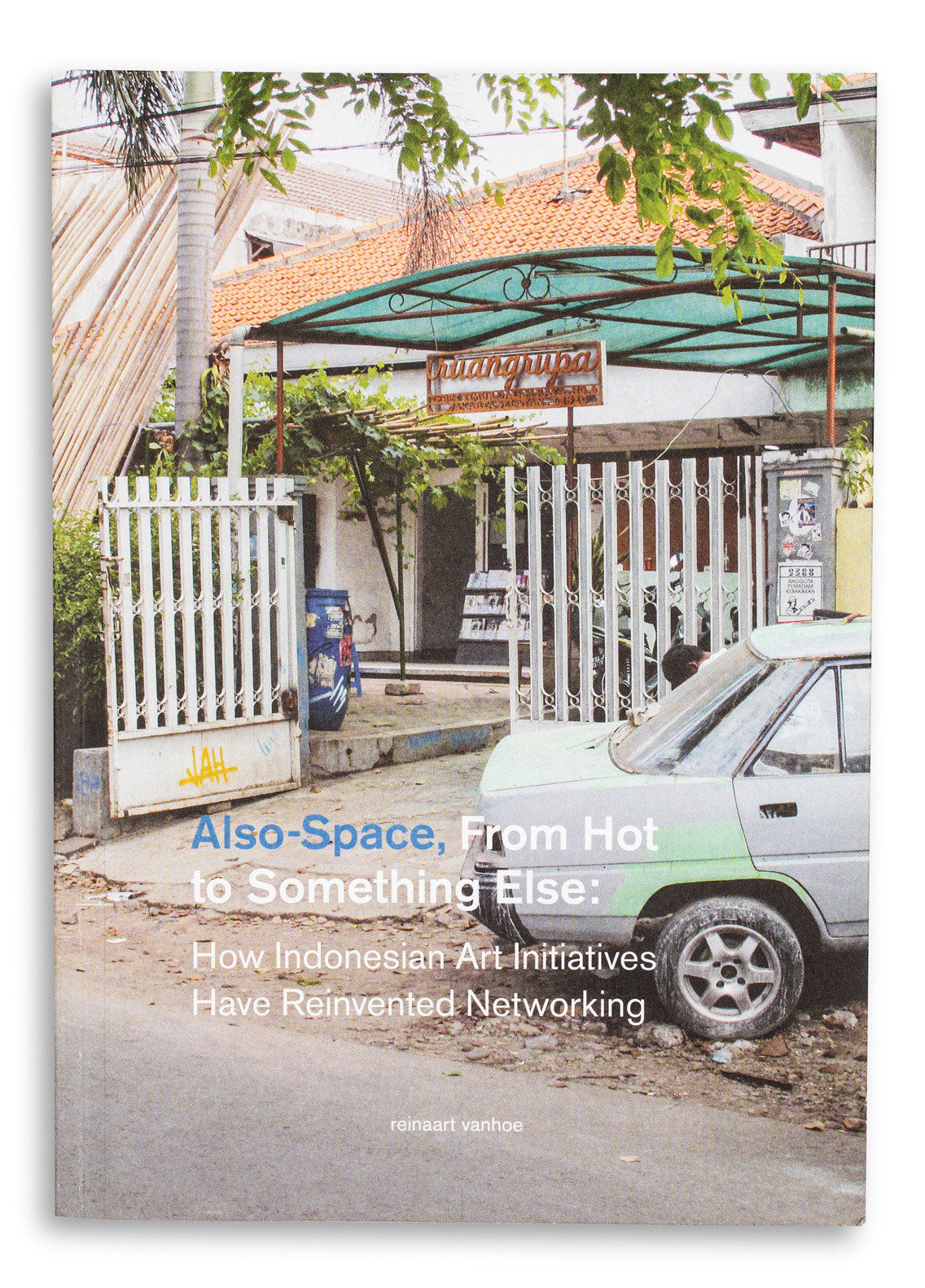

As a pilot project, Hybrid Publishing has developed a collaboration between teachers, graduates and designers where two or more publications are made for projects that have won the school’s annual award for outstanding Bachelor’s and Master’s graduation research. This award encompasses both graduation thesis and, more importantly, the research within the graduate’s art or design project. Examples include photographic research on the Dutch asylum system by Lou Muuse (2016)—with the conclusion that it has been designed to make obtaining asylum nearly impossible, the throwing away of roadkill meat as an environmental and ethical issue by Daisy Thijssen (2017) and the possible reconfigurations of interiors through artificial intelligence where “form follows algorithm” in Merle Flügge’s graduation research (2018). The respective research publications exist both as downloadable, visual e-books (or e-brochures) and as physical books in the shapes or materials of Chinese luggage bags, supermarket flyers and interactive media objects. (A forthcoming publication, Tingling by Tracy Hanna, will be a vinyl LP.) In all these examples, new publishing formats were necessitated by the combination of visual and multidisciplinary research where the artists and designers ventured into the fields of investigative journalism and political science (Muuse), ecology and ethics (Thijssen) and computer science and media studies (Flügge). Other WdKA Hybrid Publishing publications have included research about bio design and bio engineering.

If one considers these (small) publications test cases for larger, multidisciplinary research projects, then their implication is obvious: Beyond merely changing the presentation of existing research, they address the forms and practices that multidisciplinary research should take as such: where artistic, visual and performative practices serve as neither observation cases (like in art history) nor mere illustrations of academic research (like in scientific visualisation), but as equal partners with the humanities and the social and hard sciences. A good example is the current RASL research project GAmeful Music Performances for Smart, Inclusive and Sustainable Societies (GAMPSISS) in which music composers, visual designers, social and technological scientists investigate the potential of fusing classical music and gaming in order to foster listening culture. The Hybrid Publishing approach could help to not only document but also integrate the auditory-musical and ludic devices developed in this project in the final research publications.

Aside from that, Hybrid Publishing is not only concerned with the form and media of research publications but also their dissemination. The rule that all Hybrid Publishing projects should exist in both print and electronic form, where both are developed in one comprehensive process (as opposed to the one being made as an afterthought to the other), is strongly informed by an Open Access ethic according to which research should be freely and openly accessible to anyone. This is a particularly urgent concern for art schools all over the world. While having much higher research ambitions than in the past, most of them lack university-level research libraries. In the meantime, the Dutch government has signed a treaty according to which Open Access publication will become the norm in the country’s higher education by 2020. The ambitions of Hybrid Publishing are thus no longer experimental but address a mainstream educational demand.

Looking back

Historically, hybrid or experimental publishing is not a new phenomenon, neither in the arts and design nor in academia. Both the visual and dissemination forms of book knowledge have been debated for almost an entire century. In a manifesto published in artist Kurt Schwitters’ art periodical MERZ in 1923, the Russian Constructivist artist and designer El Lissitzky sketched, in eight bullet points, a program for the “new book”. Among other conditions, this book should be designed as a “book-space” that gives “reality to a new optics” (as reprinted in Lissitzky-Küppers, 1992, p. 359). Instead of just giving a new look to existing content, the “new book demands a new author” and Lissitzky’s manifesto concludes with the demand that the “printed sheet . . . must be transcended: THE ELECTRO-LIBRARY” (Lissitzky-Küppers, 1992, p. 359).

While the “electro-library” remained a purely speculative vision, Lissitzky’s book designs from that time anticipate many principles of what is called in the 21st century, “new media”. In 1923, Lissitzky met Piet Zwart, who taught at what is now Willem de Kooning Academy, in addition to his work as a commercial designer.[ref]Zwart became controversial at the school for his demand, first published in 1928, to shut down “the fine art painting program” in favour of “synthetic and visual drawing, advertising, modern reproduction technologies, typography, photography and its visual possibilities, film, and the use of colour in architecture and in the urban space” (Zwart, 2007, p. 26). This lead to the school ending his contract in 1930.[/ref] Lissitzky’s, Schwitters’ and Zwart’s graphic designs were prominently featured in typographer and designer Jan Tschichold’s 1928 book The New Typography. Similar in format and style to the Bauhausbücher(Bauhaus books)—including László Moholy-Nagy’s Painting, Photography, Film from 1925—Tschichold’s book became the canonical textbook of 20th century modernist type and graphic design. In their new form and content, the Bauhausbücher marked a high point of artistic research publications in the early 20th century. The Danish CoBrA painter and Situationist Asger Jorn likely coined the term “artistic research” in his 1957 “Notes on the Formation of an Imaginist Bauhaus” when he wrote: “Artistic research is identical to ‘human science,’ which for us means ‘concerned’ [i.e. engaged] science, not purely historical science. This research should be carried out by artists with the assistance of scientists”. Jorn’s own experimental artistic research publications include “psychogeographic” atlantes of Copenhagen and Paris created in collaboration with theorist and Situationist founding member Guy Debord. Their city cartographies are radically subjective instead of scientific, containing collages of torn-apart maps, paint drops and glued-in materials found in the streets.

Moholy-Nagy’s books were a major influence on Marshall McLuhan and the formation of his media theory of the 1960s. Painting, Photography, Filmfocused on what were the new media in the 1920s, discussing them as subjects and aesthetic challenges in their own right rather than as mere tools for image making. When McLuhan taught his first university course in 1938, he put Moholy-Nagy’s books on its syllabus. McLuhan remains one of the few humanities scholars who engaged in artistic research and experimental publishing as part of his scholarly work: First, with Counterblast (two versions published in 1954 and 1969), a riff on Wyndham Lewis’s 1915 experimental-typographical BLAST magazine (which is a classic of 20thcentury experimental publishing); second, with the book The Medium is the Massage, his collaboration with the graphic designer Quentin Fiore from 1967, in which a typing error (“massage” instead of “message”) in the editorial process ended up becoming the title of a book that presents media theory in a visual publication. Other historical examples of academic publishing that transgress the boundaries of scholarship, visual art and design include Jacques Derrida’s experimentally written, non-linear, multi-column philosophical text Glas (1974) and the book Diagrammatic Writing (2014a) by Johanna Drucker, who is both an accomplished contemporary artist making artists’ books and a humanities scholar.

Scholarship has conversely migrated into audiovisual media in order to be more accessible and reach wider audiences, an approach practiced in British cultural studies and American postcolonial studies, such as in John Berger’s BBC television program Ways of Seeing (1972) and Henry Louis Gates’ African American Lives (2006). The recent explosion of racist and conspiracy theory-mongering pseudo-science, as well as the stardom of such scholarly questionable (as far as his analysis of Derrida and “Postmodern Neo-Marxism” is concerned) academics as Jordan Peterson on YouTube, indicates an urgent need for researchers to more seriously engage with and become visible on these channels. Yet on closer inspection, and with the single exception of Drucker’s Diagrammatic Writing, the aforementioned books and television programs qualify as “creative scholarship” rather than as “artistic research” in Jorn’s sense: The hierarchy and the respective roles of writer/scholar and visual designer/artist are not really removed but just softened through intensified collaboration.

In the espousal of 1920s avant-garde concepts by experimental forms of humanities publishing after the Second World War, Lissitzky’s vision of the “electro-library” was initially not taken up at all. Instead, it continued—likely without any awareness of Lissitzky’s manifesto and initially without involving artists and visual designers—in information science and computer engineering, such as in the 1940s “Memex” architecture of interlinked microfilm documents by American presidential advisor Vannevar Bush, which influenced Theodor Holm Nelson’s 1963 concept of electronic “hypertext”.[ref]Paul Otlet’s index card-based information systems, created in Belgium between 1895 and 1934, were forerunners of modern search engines. Bush’s essay “As We May Think” and key passages of Nelson’s book-manifesto Computer Lib/Dream Machines are included in (Wardrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003). These texts greatly influenced the original architecture of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s[/ref] In recent years, extensive “electro-libraries” in Lissitzky’s spirit have been realized in non-profit projects like the Internet Archive (https://archive.org) and the artist-run UbuWeb (http://www.ubu.com), Aaaaarg (https://aaaaarg.fail) and Monoskop (https://monoskop.org)—the latter being founded and maintained by Piet Zwart Institute graduate Dušan Barok. They are vast repositories of freely downloadable, audiovisual media and digitized modern and contemporary art and philosophy books, serving as the unofficial research libraries of art schools around the globe. Their mere existence proves the need for rethinking the forms and dissemination modes of published research.

Perspectives

A future ambition for the WdKA Hybrid Publishing lab is to interweave artistic research within RASL with experimental and hybrid publications. In doing so, it should act not as a design bureau but as a research partner. Models for this do not only exist in experimental scholarship like McLuhan’s and Gates’, but also in contemporary art that transgresses the boundaries between visual art, visual culture research, essayism and critical theory. This type of art has gained prominence in the last couple of years: examples include the video works of John Akomfrah and Hito Steyerl; Adrian Piper’s work that exists in between conceptual art, academic philosophy and social critique; and the design research of the Metahaven design collective (consisting of WdKA alumni Daniel van der Velden and Vinca Kruk).

The question remains whether such work will conversely inspire new forms and non-traditional media in academic scholarship, continuing where McLuhan, Derrida and others left off. New partnerships between art and scholarship could also be forged for empirical research with its increasing reliance on complex (often also interactive and real-time) visualizations for which traditional paper and textbook formats are no longer adequate, and where visuals are no longer just illustrations but amount to—as (Drucker, 2014b) puts it—“forms of knowledge production”.

New collaborative, audiovisual and Open Access forms of research publishing radically question the current status quo of academic book and journal publishing. Clearly, the renewal of publishing has to come from art and critical scholarship, as it can no longer be expected from a conservative publishing industry that, for the most part, is preoccupied with guarding its territory.

Conversely, publishing as an ethos of sharing challenges the arts: If they can no longer be legitimized through the Western cultural canon, if contemporary art becomes too corrupted by art market speculation to still be credible as a critical practice, if visual culture from outside the art and design field becomes more influential for culture at large, what needs to be done? Could artistic research contribute to rethinking art practice as publishing practice?

References

Bush, V. (2003). As we may think. In N. Montfort & N. Wardrip-Fruin (Eds.), The new media reader (pp. 35–48). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

De Bruijn, M., Cramer, F., Castro, L., Kircz, J., Lorusso, S., Murtaugh, M., . . . Riphagen, M. (2015). From print to ebooks: A hybrid publishing toolkit for the arts. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Institute of Network Cultures.

Derrida, J. (1974). Glas. Paris, France: Éditions Galilée.

Dibbs, M. (Producer), & Berger, J. (Writer). (1972). Ways of seeing [Television series]. London, England: British Broadcasting Corporation.

Drucker, J. (2014a). Diagrammatic writing. Eindhoven, Netherlands: Onomatopee.

Drucker, J. (2014b). Graphesis: Visual forms of knowledge production. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Flügge, M. (2018). Supertoys supertoys. WdKA Hybrid Publishing. Retrieved from http://hp.researchawards.wdka.nl/supertoys.html

Gates, H. L. (Executive Producer). (2006). African American lives[Television series]. Arlington, VA: Public Broadcasting Service.

Jorn, A. (1957). Notes on the formation of an Imaginist Bauhaus. In Bureau of public secrets. Retrieved from http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/bauhaus.htm

Lissitzky-Küppers, S. (1992). El Lissitzky: Life, letters, texts. London, England: Thames & Hudson.

Ludovico, A. (2012). Post-Digital print: The mutation of publishing since 1984. Eindhoven, Netherlands: Onomatopee.

McLuhan, M., & Fiore, Q. (1967). The medium is the massage: An inventory of effects. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

McLuhan, M., & Gordon, W.T. (2011). Counterblast: 1954 facsimile. Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press.

Moholy-Nagy, L. (1969). Painting, photography, film. (J. Seligman, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Muuse, L. (2016). Return to sender. WdKA Hybrid Publishing. Retrieved from http://hp.researchawards.wdka.nl/returntosender.html

Nelson, T. H. (2003). From computer lib/dream machines. In N. Montfort & N. Wardrip-Fruin (Eds.), The new media reader (pp. 301–338). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Parker, H., & McLuhan, M. (1969). Counterblast. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace & World.

Thijssen, D. (2017). Meat market. WdKA Hybrid Publishing. Retrieved from http://hp.researchawards.wdka.nl/meat-market.html

Tschichold, J. (1987). Die neue typographie [The new typography]. Berlin, Germany: Brinkmann & Bose. (Original work published in 1928).

Willem de Kooning Academy. (2018). ‘Hybrid Publishing’. WdKA. 2018. https://www.wdka.nl/research/hybrid-publishing.

Zwart, P. (2007). Nederlandsche ambachts- en nijverheidskunst [Dutch crafts and industrial art]. In F. Huygen, Visies op vormgeving [Visions on design] (Vol. 1, pp. 25–27). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Uitgeverij Architectura & Natura.