Graduate in graphic design and biochemistry. Or become a songwriter and political scientist. That’s possible at the Rotterdam Arts and Sciences Lab, where students can combine an academic bachelor’s degree with an art degree. “The programme is essential”, according to programme coordinator and practical expert Boo van der Vlist, “because all the problems we face as a society in the 21st century are too complex to approach from a single discipline.”

Do you choose an academic career or do you follow your artistic ambitions? Do both, they say at the Rotterdam Arts and Sciences Lab (RASL). In 2016, RASL introduced the Double Degree where students work towards both an academic bachelor’s degree from Erasmus University Rotterdam and an art degree from Codarts or the Willem de Kooning Academy.

But what can you do in practice with this combination of art and science? Boo van der Vlist (28) has unique experience. Besides coordinating the RASL Double Degree programme, she is an artist and an academic. “At the art academy, I felt that my research skills were underused. A lot of my work was socially and politically oriented, so I thought I’d go and study political science to give me a better understanding about the world my art relates to. At first, I just did some courses, but suddenly in 2016 I’d completed my master’s!”

And then?

(laughs) Yes, that’s the thing. I still can’t and won’t choose. And that will continue for the rest of my life. I want to use the skills of both the arts and sciences that I’ve acquired in my studies and professional work. After my studies, I started working with the Arts department of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science where art, policy and research came together nicely. I became the project manager for a conference called “Cultuur in Beeld”. At the same time, I was doing my own art-research project into community initiatives, called “Amsteldorp Ontdekt”. Both projects were transdisciplinary, but each required its own skillset. You could say that my work at the Ministry required more of my academic skills and in Amsteldorp, my artistic abilities. However, I think my diverse skillset added value to both projects.\

What does transdisciplinary mean?

A project is transdisciplinary when different disciplines come together, not just by taking bits from each other here and there but when they really integrate. Boundaries become blurred, things no longer fall into a single category. So in my case, it’s not either “policy” or “artistic creativity”. You use the skillsets of both domains at the same time.

What is your favourite example of this from your own work?

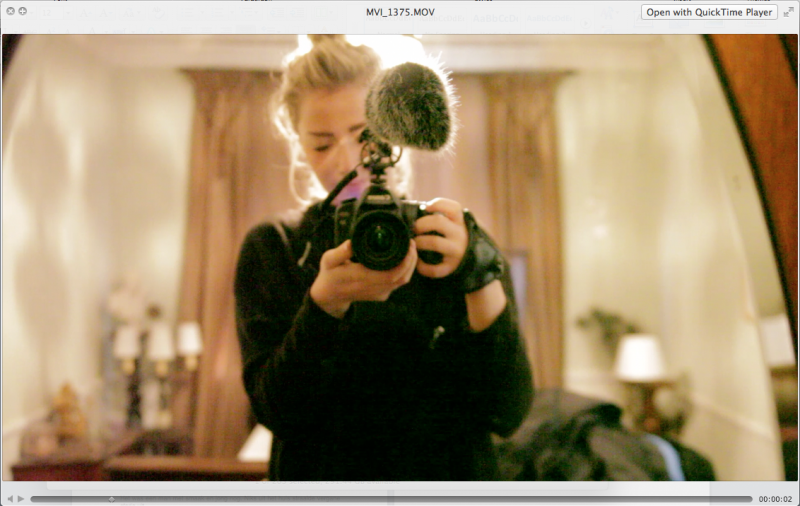

That would be my graduation piece about De Loods that I completed at the Sandberg Institute. De Loods is this big warehouse/second-hand shop near the centre of Amsterdam, and I was in there one day and thought ‘Wow, something’s happening here!’ I can’t exactly say what makes this place so special, but it really is amazing. Each layer of society comes together here, such as the everyday shopper, the vintage collector, the artist, and community cohesion just happens without having to set up a communal programme first. How does it happen? Unfortunately, many of these places are disappearing due to gentrification. And I wanted to know what is going to be lost from this process, because if you have more insight into the power of such a place, it’s easier to incorporate this quality in urban redevelopment. I studied De Loods through what I would call an “artistic” version of ethnographic research during an internship. I spent nine months working alongside the guys at De Loods, going with them to clear houses, talking to people and taking photos and videos. So I needed my skills as an artist on the one hand and those of a researcher on the other.

What insights did that produce that a “normal” sociologist wouldn’t have gained?

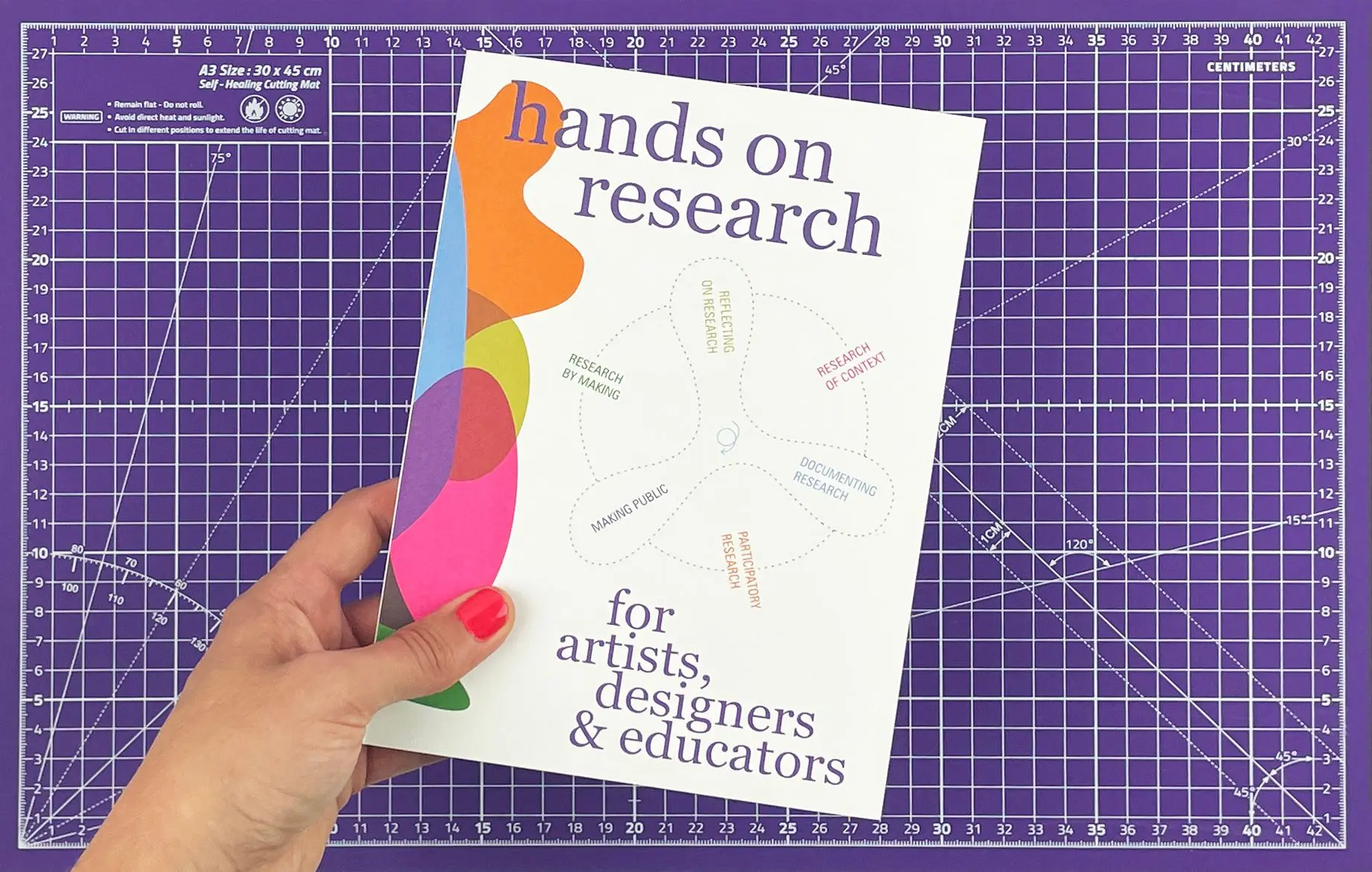

I think a very important aspect is recording “soft” data, which is based on more of an instinctual approach. For example, some people are a hero in their community. But why? And how do you harness their strengths for the community? You won’t find out if you just knock on someone’s door and ask them ‘Tell me what you’re good at?’ Often people don’t know. You have to trust your gut feeling and act and observe. At the same time, it’s important to translate your ideas and research into something that people can use. With De Loods there was much more flexibility in presenting the results than what would be allowed in a “pure” sociological survey. I produced a book describing my experiences and I used a lot of images to visually communicate my research, as opposed to employing a more typical scientific approach of writing about my results and conclusions. I also translated all my insights from my community projects into a new approach for urban development, which I call the inbetweener methode.

And what is the “inbetweener” method?

It’s a method specifically for urban design and planning. Many districts are being demolished and redesigned in the name of urban development. City planning is based too much on hard parameters of the population, like social status, money and education. And many areas are being redeveloped with the goal of attracting “this percentage of highly-educated people and young potentials”, in order to improve the economy in the city. If there’s too much focus on these parameters, other parameters are jeopardized, and the city will only be a place for highly-educated, rich people, with a clash between the centre and the periphery. I find it much more interesting to include the “soft” data, the history and culture of the place, in the redevelopment. What are the skills of the residents? What are the locations that have already been proven to function? Who are the heroes in the community? These parameters are essential in building communities, but during the redevelopment of a neighbourhood the interests of the residents are often at odds with those of the municipality. An “inbetweener” is someone who can move between the two worlds and can grasp the “soft data” and incorporate these social parameters into the redevelopment process with the municipality.

Is the world actually prepared for the insights arising from transdisciplinary research?

I think it’s a matter of understanding the limitations in our current approach to research and having the right tools to integrate new insights. In the case of wicked problems, such as climate change and urban development, there’s often one dominant group who determines the problem. But if you define a wicked problem as just one problem, the solutions also become and stay limited. Take the climate crisis. It’s such a complex, huge problem which involves everyone in some way or other. Do I buy a plastic bag in the supermarket or not, what do I eat, and should I cook with gas or electricity? You can’t find a single solution to wicked problems. What you need is an approach whereby you experiment: do things, take action and through action discover new ways of looking at the problem and create opportunities.

How do we ensure that there’s a connection between a transdisciplinary approach and the one-dimensional way in which the world hopes to solve problems?

Obviously, it’s not the case that only transdisciplinary people can tackle these problems. This has to be done in partnership with people who are trained in one discipline, because it’s valuable to be able to focus on one discipline and become an expert in it. It’s particularly important to involve every expert from the beginning and to start a conversation that goes beyond one-dimensional thinking, and I think you need “inbetweeners” for that. I believe that “inbetweeners” are better able to take a holistic approach.

Which domains can benefit most from a transdisciplinary approach?

I really think all domains, because the problems we face are too complex to tackle from just one discipline. Everything is transdisciplinary. In health care, for example, they already ensure that more people and parties are involved in the problem. If someone is mentally unwell, then it’s not just about health but also about safety and support. You involve several knowledge domains and people. People only create monodisciplinary compartments because it helps them understand the problem better. Our task is to show people that we shouldn’t compartmentalize but use networks. The world is changing rapidly and we need to respond faster. We invent systems, but when they’re ready for use the situation has already changed. The question is therefore, how do we make the system flexible enough?

You coordinate the RASL programme from Erasmus University College. How do you contribute to that necessary flexibility through that work?

Young people don’t tend to compartmentalize as much as older generations. The great thing about the Double Degree is that students do two studies, and you can do that in five years instead of seven. We make sure that exams don’t coincide with each other and that timetables can be combined. For the Double Degree we mostly facilitate the coordination of the two areas of study so that students don’t have to choose between their academic and artistic ambitions.

We don’t yet provide joint-degree programmes at the intersection of the studies. However, you find that Double Degree students more naturally tend to use knowledge from one domain for their other study. For a course at the Willem de Kooning Academy, I gave an assignment asking students how we can make gentrification inclusive. One RASL student developed a scientific test to determine what prejudices we take into shops. She clearly used her scientific research abilities for a creative assignment.

Is that hybrid approach the future of the RASL Double Degree?

We’ve just been awarded a Comenius grant to perform research into the development of transdisciplinary education. How do you achieve that and what does it look like? We’re thinking of working towards a joint master’s degree, so a transdisciplinary research programme. And we’re also working on a minor within the Double Degree where students can get that cross-pollination. We also need to consider how to shape this kind of transdisciplinary education. It could be interesting to let the students design this type of programme. For example, a student could do a project for both institutes where they determine the content or research topic and put together the teaching team from the different institutes. I would like it if teachers then have to explore how to evaluate the work so that at the end, one grade counts in both institutes. It would mean that teachers would also need to think in a transdisciplinary way.

Are there plans to introduce transdisciplinary research for PhD students?

We’re looking at that now. I’d love to do long-term transdisciplinary research into community initiatives, for example. But the existing structures in the world of education don’t always facilitate that. Who finances such a programme that hasn’t been done before? It’s still not clear who will pay for the combination of artistic and academic research: the art or the academic world? Or do we need a new source of funding? They’re dull but very relevant questions. Through the Comenius grant, we have a budget to experiment with this in education, and we want to demonstrate that hybrid research has value. We hope that this will create more opportunities to approach education and research in a transdisciplinary way.

What type of students do this programme? Are they all all-round Leonardo da Vinci’s?

There are many different motivations for a Double Degree. Some students say: as an artist, I’m very interested in an exploratory approach. They have a concrete idea of what they want to do, so you could call them the Da Vinci’s. But there are also students who are unwilling to choose a single path after secondary school, because they’re smart and creative, they have wide interests and are academically oriented. That’s something they don’t want to lose. And that’s a very good motivation to start on a degree like this.

Are there any disciplines that are totally unsuitable for this programme?

There might be some people who don’t want to work in a transdisciplinary way because, for example, it requires a certain curiosity and mindset. But I don’t believe that there is any discipline that benefits from staying in its own compartment. You always need to have contact with the outside world. I don’t think there are any disciplines that require staying in a cocoon to deliver quality.

The first students started in 2016 and will have finished in three years’ time. How do you ensure that they succeed in what is often a monodisciplinary world?

The world isn’t so mono you know! There are more and more questions that we can’t answer, like the climate crisis, health care and security. In all of these issues, there’s room for experimentation, for transdisciplinarity, for combining disciplines and domains. Our students will enter a world that’s begging for people who can do that, who can speak different languages, who are creative and flexible in their way of thinking. That need is very strong and will become stronger.

Boo van der Vlist in 10 choices

To find out who Boo van der Vlist is, we asked her to make ten choices. What if she can’t combine domains but has to make choices?

Artist or researcher?

Artist.

Chocolate sprinkles or peanut butter?

Peanut butter.

Researching or teaching?

Teaching.

Calling or texting?

Calling.

Erasmus University or University of Amsterdam?

Erasmus.

Drink or drugs?

Drink.

One student a 10 and the rest a 4, or all a 7?

All a 7.

Smart or funny?

Funny.

Dull and effective, or experimental and imperfect?

Easy: experimental and imperfect.

Family or friends?

Family.