Trans/disciplinary Practices in the Age of Climate Change

When talking about the relation between the arts and sciences, one cannot ignore the ground-breaking lecture by the British novelist and scientist C.P. Snow (1959/1990), in which he criticizes the strong division between what he calls “the two cultures”. Snow concluded that the intellectual life of western society was radically split into two cultures, with the sciences on one side and the arts-humanities on the other. With an eye for detail, he described the different worlds of his scientific and literary friends, who would occasionally peek over the walls of their separation, only to retreat as fast as possible to their own worlds: “there seems to be no place where the cultures meet” (Snow, 1959/1990, p. 172). According to Snow, both parties are not only “self-impoverishing” themselves with this strong division but are also shaping a hindrance to solving the world’s problems. “At the heart of thought and creation we are letting some of our best chances go by default”, he claimed, concluding that “there is only one way out of all this . . . by rethinking our education” (Snow, 1959/1990, p. 172).

While Snow’s lecture proves that this pivotal discussion already dates back to the 1960s, and while one can trace a history of artistic experiments in art-science relations from the 1960s and 1970s and all the way up to the present, it is surprising to note how long it took before these concerns were taken up as a serious challenge in education. In the 1990s, Leonardo, an international magazine on the use of contemporary science and technology in the arts, concluded that “in a new multidimensional universe created by science and technology, art educators still teach what used to be. . . . Although new areas of interface between art, science and technology are sprouting up all over the world, the vast majority of institutions are only adding new media to old structures” (Sheridan, 1990, p. 165).

Entering the 21st century, things have luckily changed for the better in several respects. Internationally, within higher art and design education, interdisciplinary curricula and master programmes have been and are being developed, although secondary and vocational education seems to be lagging slightly behind in this development. At universities, one can witness a proliferation of new study paths and an increase in interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary education, already available at the bachelor’s level.

In the Netherlands, this recently led to the concern—voiced in the national newspaper NRC Handelsblad by “The Young Academy”, a platform of young researchers from the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences (KNAW)—that students are no longer grounded enough in disciplinary knowledge. According to these researchers, an interdisciplinary approach has an added value but should not come at the expense of existing disciplines (Huygen, 2018). Finding the right balance with the exchange of disciplinary and interdisciplinary knowledge is indeed important, but what seems to be really at stake is not only the renewal of education within art academies on one side and universities on the other but also the effort of cutting through the duality of the education system, currently being steered by the founding of new research consortiums across both worlds. Both the Rotterdam Arts and Sciences Lab (RASL) and the Amsterdam Research Institute of the Arts and Sciences (ARIAS) are examples of these new models of research.[ref]The Rotterdam Arts and Sciences Lab (RASL) is a collaboration between the Willem de Kooning Academy, Codarts Rotterdam and Erasmus University Rotterdam. The Amsterdam Research Institute of the Arts and Sciences (ARIAS) is a research platform by the Amsterdam University of the Arts (AHK), Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (HvA), University of Amsterdam (UvA) and Vrije Universiteit (VU).[/ref]The purpose of these cross-disciplinary consortiums is to uncover intersections and cultivate encounters and collaborations between artistic research and research in the humanities and social sciences. The collaboration between artistic research and other disciplines aims to shape debates, raise alternative research questions and sketch speculative horizons of research by contributing to urgent research questions connected to the urban environment, new forms of education and “critical making”, digital and techno-scientific culture, climate change and migration.

This might seem to be an overly ambitious agenda at first sight, and a certain sense of modesty and realistic perspective on what one is effectively able to contribute to these so-called “wicked problems” is indeed needed. Nevertheless, this article will try to argue that we live in a time which asks us to think across disciplines as an inevitable new reality. The much debated notion of the Anthropocene has spurred the humanities to a renewal of their research agendas and practices and a reconsidering of disciplinary boundaries. Taking climate change as an example, this article explores how the urgency of this topic has resulted in an international discourse, amongst academics and cultural practitioners alike, about the necessity of thinking across the arts-sciences divide and developing new transdisciplinary practices.[ref]For an apt description of the difference between inter-, multi-, post-, and transdisciplinarity, see Lykke (2018).[/ref] International scientific publications from different academic disciplines are increasingly putting this subject up for debate, specifically with regard to the agency of the artistic-design field in relation to climate change, and artists and designers are exploring transdisciplinary practices in response to climate change in practice and have been doing so for over a decade. Studying these practices might help us to get an idea about not only how arts-sciences collaborations work and play out in practice but also how they might inspire educational, curricular developments in the future.

From matters of fact to matters of concern

Before I write more on how and why climate change as a many-headed monster urges us to think differently about disciplinary divisions, I would like to take a small detour to recent developments in philosophy. Within critical philosophy and the philosophy of science, several contemporary philosophers and academics such as Karen Barad, Bruno Latour, Isabelle Stengers, Donna Haraway and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, amongst others, have already successfully complicated as well as neutralized the disciplinary divide between the arts and sciences.[ref]See Barad (2007), Haraway (1988), Latour (2004b), Stengers (2005) and Tsing (2015).[/ref] They have put decisive arguments on the table against the division of the arts-humanities and the natural sciences into radically different knowledge epistemologies, each arguing in their own way for a new kind of realism which transcends the classic object-subject dualism and makes a shift “from matters of fact” to “matters of concern”, as framed by Latour (2004a).

“Matters of fact” in this case refer to the tradition of empirical, factual and objective knowledge attached to scientific research. According to Latour (2004a), in this day and age in which scientists deal with politics, grants and industry—in other words, a myriad of factors in a large and complex, interlinked field—the so-called objective stance of scientific truth no longer bears the same weight or has the same meaning as it used to have. Inspired by Karen Barad, Latour makes a plea for a new kind of “realist” empiricism which takes into account the notion of “matters of concern”, as opposed to “matters of fact”, not to get away from the facts but to get closer to them. This realist position means acknowledging and specifying one’s position as a scientist (never taking this for granted behind a shield of objectifiable truth) and also being aware and taking into account the networked reality in which this research takes place. Not only will matters of fact (factual, objective truth) and matters of concern (the political, the agency of the researcher interlocked in a field of multiplicities) always be inseparable, but according to a more materialist account of reality, we also cannot overlook the complex interaction of relations and actants attached to objects in their own right. Latour (2004a) therefore asserts that we have to start thinking in terms of “multiplicity”, not in terms of “substraction” (p. 232). A researcher is not the one “who debunks, but the one who assembles . . . the one who offers the participants arenas in which to gather” (Latour, 2004a, p. 246).

In this arena the arts, as a wide variety of aesthetic and creative practices, and the sciences should be seen as multiple and situated rather than singular and universal(Latour, 2004b; Gabrys & Yusoff, 2012, p. 16). In line with this, professor Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova, curator and artistic director of the Base for Contemporary Art (BAK: Basis voor Actuele Kunst) in Utrecht, write in their recently published Posthuman Glossary: “More than ever we need to bring together interdisciplinary scholarship and even aim at a more transdisciplinary approach in order to embrace the complexity of the issues confronting us. The parallelism of science, philosophy and the arts—so dear to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari—is more relevant than ever in this endeavour” (2018, p. 10).

Although one might think this is typically a kind of plea originating from the humanities, both Isabelle Stengers and Karen Barad build up their arguments starting from the “hard”, natural sciences. (Stengers studied chemistry and Barad holds a doctorate in theoretical physics.) Barad (2007) coined the by now famous concepts “agential realism” and “intra-action”. Inspired by the study of quantum physics, she claims: “We are not outside observers of the world. Neither are we simply located at particular places in the world: rather we are part of the world in its ongoing intra-activity” (Barad, 2007, p. 184). According to Barad, subject and object do not pre-exist as such but emerge through intra-actions. Instead of privileging one discipline and reading others against it, we should think in terms of “transdisciplinary engagement” and attend to the fact that boundaries between disciplines are not pre-set but actively constructed (Barad, 2007, p. 91). The boundaries between disciplines can be questioned because they are part of a material-discursive practice: “Practices of knowing are specific material engagements that participate in the (re)configuring the world. Which practices we enact matter—in both senses of the word” (Barad, 2007, p. 91).

Similarly, according to Stengers (2000), science is much more than gathering facts and data, and she aptly describes the dichotomy between “matters of fact” and “matters of concern” as follows: “Every scientific question, because it is a vector of becoming, involves a responsibility” (p. 148). It calls on “one’s capacity to feel: the capacity to be affected by the world, not in a mode of subjected interaction, but rather in a double creation of meaning, of oneself and the world” (Stengers, 2000, p. 148). Stengers also questions the idea of having strictly defined boundaries between disciplines and instead favours the idea of what she calls “an ecology of practice”. Disciplines and practices are not static, as there are always “new possibilities for them to be present, or to connect” (Stengers, 2005, p. 186). In this definition, practices are not defined by their pre-set or predefined boundaries but by their continuously evolving status, which might also include cross-overs, the shifting of boundaries or the birth of new practices and disciplines.

The cultural turn in climate change research

The recent views in critical philosophy described above are concerned with contesting not only the object-subject duality in scientific research but also the other deeply ingrained dualities inherited from humanism such as nature-culture or human-non-human as well. It therefore comes as no surprise that a particularly wicked problem such as climate change, challenges our thoughts about the arts-sciences debate. In recent years, scholars have called for “strengthening the integration of social sciences and the humanities in the global environmental change research” and even more importantly, in the context of this article, for an overall “cultural turn” in climate change studies and action (Galafassi et al., 2018, p. 72). I would like to single out two lines of argument in this discussion: one displayed in an article entitled, “’Raising the Temperature’: The Arts in a Warming Planet”, co-written by a large number of authors from different universities with the main author being affiliated with the Stockholm Resilience Centre (Galafassi et al., 2018); and one displayed in two articles co-written by Jennifer Gabrys, professor at the Department of Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London and Kathryn Yusoff, professor at the School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London (2011, 2012).

Gabrys and Yusoff (2011) begin with the premise that climate change is as much a political, social and cultural event, as it is a scientific one. This is underlined by Galafassi et al. (2018) in their article which states that “as climate change impacts biophysical, social, economic and political systems, it is best seen not solely as a technical problem but as a challenge requiring cultural, adaptive and creative responses” (p. 71). A concentration on scientific, technological and economic approaches to climate is replaced by an attention to climate as a dynamic, cultural and societal force. In other words, according to both viewpoints, climate change is being re-imagined as an ethical, societal and cultural problem.

Galafassi et al. (2018) conclude: “The multifaceted challenges of climate change cannot be addressed by science alone . . . Improving societies’ capacities to respond to climate change requires an open and engaging transdisciplinary process with large and diverse populations and reimagining public goals” (p. 73). Based on literature research, they list an extensive set of possibilities of the potential role that the arts can play in climate change transformations. They mention, for example: creative imagination and serendipity, storytelling, exploring futures imaginatively, science communication and possibilities for political engagement, pre-figuring potential futures through direct action, transdisciplinary learning processes of knowledge integration, awareness of more-than-human worlds and the embrace of social-ecological complexity (Galafassi et al., 2018, p. 74). The authors also have witnessed a significant increase in activity of artists engaging with climate change from the late 2000s onwards. They conclude that “art in climate transformations is best seen as an open inquiry process, unconstrained by standard scientific methods, and involving not just artists and scientists but also communities and change agents across multiple domains of action” (Galafassi et al., 2018, p. 77). However, the article does not dive any deeper in the material specificity or differentiation of these practices, nor does it provide examples of the artists or designers attached to them.

This is where Gabrys and Yusoff make a difference, providing several examples while making the processes behind the artistic practices more tangible. According to the authors, the imaginative practices of the arts and humanities play a critical role in thinking through the representations of environmental change. But rather than reducing the arts to a process of social learning, they pay attention to the mutual and equivalent exchange of the arts and sciences. Arguing against “deculturing” climate change, they conclude: “Rather than define arts and sciences as separate disciplines in need of intersection, however, many new creative and scientifically informed practices are emerging that focus especially on new opportunities for political participation and public engagement with climate change” (Gabrys & Yusoff, 2011, p. 518). They describe three characteristics of these “new cultures of climate change” in the arts and design: firstly, the imagination of the future of climate change; secondly, the ability to develop adaptive strategies that can be embedded in everyday practice; and lastly, the critical engagement with the practice of climate science (Gabrys & Yusoff, 2011).

Speculation, science/fiction

The first example that Gabrys and Yusoff (2011) mention of “the new cultures of climate change” is futurity. As an area of study, futurity has received increasing attention in climate change studies, particularly in relation to risk management and scenario building. But according to these authors, not enough attention is paid to cultural and creative methods of environmental imagining, nor to how the arts and humanities play an important role in thinking through representations and images of climate change and in giving tangible form to the imagination of different worlds. “Climate futures require approaches not only characterized by calculability and risk but also imaginative acts that open new spaces and practices for dealing with the effects of uncertain futures” (Gabrys & Yusoff, 2011, p. 518). Fiction, as opposed to rational approaches, can show us a changing world so that we can “experience its dislocation across social, cultural and emotional registers” (Gabrys & Yusoff, 2011, p. 521). Predictive methodologies of climate science policy differ markedly from materialist forms of knowledge. This is more akin to the descriptive arts of the humanities, in the production of probable, preferred or hoped for futures, which challenge us to recognize the changed conditions of climate change.

Gabrys and Yusoff give different examples of science-fiction literature to illustrate this aspect, but do not mention the interesting developments in and examples of speculative research and storytelling in arts and design practices. Speculative design, for instance, is seen as a means of speculating how things could be, aiming to open up new perspectives on wicked problems. By speculating, designers re-think production systems, using fiction and speculation on future products, services, systems and worlds, thereby initiating a dialogue between experts (scientists, engineers and designers) and users of new technologies or products (the audience). This presents a stark contrast to a top-down view of technology in which technology is presented as a new godlike superpower in the form of geo-engineering which will save the earth, popularized in Hollywood sci-fi productions such as Geostorm (2017) and criticized by, amongst others, the Australian professor of Public Ethics, Clive Hamilton (Hamilton, 2017).

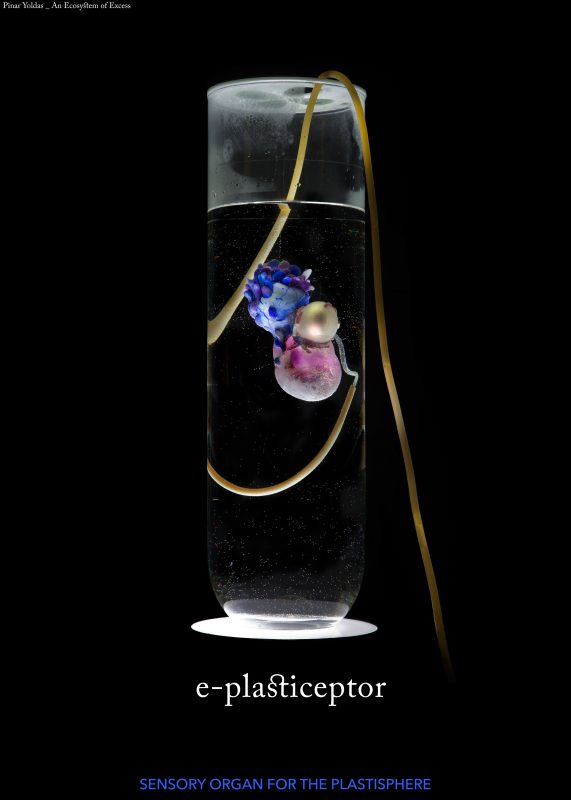

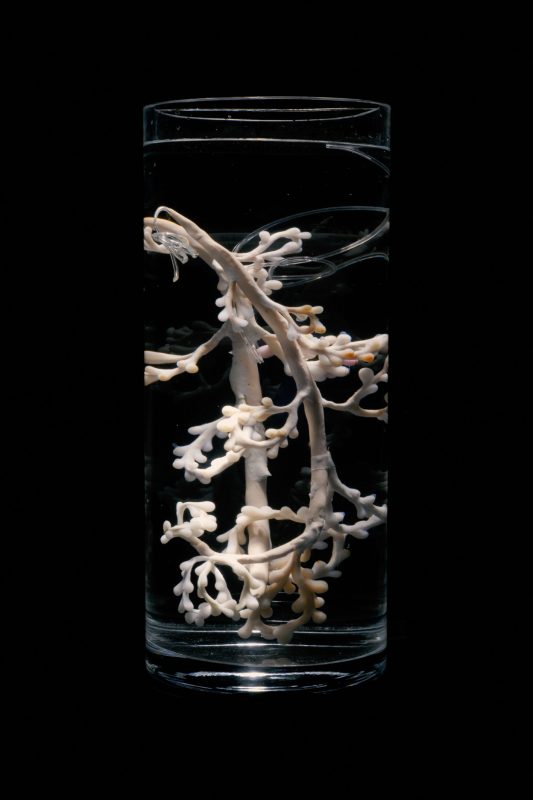

Speculative designs find part of their inspiration in science fiction, which has a long history of creating imaginary scenarios with which audiences closely identify. It is a strategy not only applied within design but also integrated in the art field and alludes to hybrid practices. An example of this is the work, Ecosystem of Excess (2014), by the artist, researcher and designer Pinar Yoldas. Yoldas studied media arts and sciences, cognitive neuroscience as well as information technologies and visual communication design, and this multidisciplinary background can be clearly recognized in her work. Her work Ecosystem of Excess is inspired by scientific research on the so-called “plastic soup”, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and the speculative presumption of how life would evolve if it started in contemporary oceans polluted by microplastics. Inspired by real-life bacteria that can metabolize plastics, Yoldas envisions and designs plants, insects, reptiles, fish and birds, and gives them organs to interact with their plastic environment. An example of this is the so-called “petrogestative” system, a digestive system specialized in crumbling hard plastics to allow for their absorption. With Ecosystem of Excess, Yoldas shows us an eerie laboratory with future species and organs. Moving in between digital technology, speculative design, biological sciences and constructed installations, as well as sound and video pieces, Yoldas has coined the term “speculative biology”. According to her, speculative biology is a form of artistic research, which involves the design of tissues, organs, organisms and biological systems in order to “catalyze creative critical thinking, thereby addressing the narrow scope of contemporary art” (Yoldas, 2016).

Re-locate-ing and re-public-ing climate change

A second example of a new culture of climate change described by Gabrys and Yusoff (2011) is the “acceptance for the need of adaptive strategies that can be embedded in everyday practice” (p. 517). Practitioners and researchers within art, design and architecture focus on climate change not as something “out there” but “in here”, entangled in contemporary local practices. If future imaginings can be thought of as a process for developing adaptive capacities and emotional resilience within changed environments, adaptation strategies offer a pragmatic alternative through iterative and local everyday practice. The built environment, land use, urban agriculture and infrastructure—the city, the community, and the scaled down unit of the home—are sites for adaptation proposals and projects, not only at the level of planning and engineering, but also through creative practice and climate-change imaginaries.

Gabrys and Yusoff (2011) provide several examples of artistic practices in this direction, mentioning the work of the New York artist May Mattingly, the British artist Nils Norman and the notorious American activist collective The Yes Men. In the context of this article, I would like to single out a work from the design collective Superflux. Superflux is a speculative design studio, which creates stories to confront the spectator with the instability of a changing world. In their installation called Mitigation of Shock (2017), they aim to show what our lives might be like, if we do nothing to combat global warming, by taking us into a flat in London—in the year 2050. While walking through the installation, the visitor receives various cues which refer to a time of extreme weather, poor air quality and world crop failures. The people living in the apartment are forced to experiment with artificially growing their own food, from mealworms and plants to oyster mushrooms, which means that half of their apartment is turned into a lab setting. As Jon Ardern, one of the two founders of Superflux explains:

The disconnect between scientific, data driven predictions of global warming, and the lack of immediately visible signs contributes to a space of cognitive dissonance . . . But it is also a space which offers the opportunity to confront our fears, to experiment with ways in which the shocks of the impact of climate change can be mitigated. We want to conduct experimental design responses to first world disasters that are likely to happen in the near future, by prototyping alternatives today. Tools, methods, materials and commons that individuals can learn, use and share in order to gain agency and capacity to mitigate the shock of climate change. (Ardern, 2016, para. 5-6)

BuggyAir (2016-ongoing) is another project they developed, which goes back to a different principle. It is an air pollution-sensing kit that parents can mount on their bikes to measure how much air pollution their children are subjected to. With a team of designers, researchers, technologists and air quality experts, Superflux built a set of ten sensor kits to be distributed among parents in London for measuring, monitoring and collecting data regarding their children’s exposure to specific air pollutants.

This is closely related to the third example of a new culture of climate change Gabrys and Yusoff refer to, namely the notion of citizen science. The topic of environmental data is often seen as an area of scientific concern. Empirical study produces observations and measurements that enter data infrastructures, which are the basis for scientific understanding and policy decisions. Yet an increasing number of creative practitioners are working with data, not just to visualize or sonify data in the context of arts-sciences collaborations, but also to question what constitutes data, to experiment with how data are produced and to recast the relationships that are articulated through data. Using visual and design strategies, artists and designers make use of a form of “radical empiricism” to try to uncover and make public what remains hidden for the general public.

As Gabrys and Yusoff (2011) describe: “Creative practitioners are now seeking to expand modes of climate science production to reconsider the social spaces of climate interaction at the science-policy-public interface . . . artists’ projects rework the scale and site of data and data generation, from the remote to the intimate” (p. 528). The visualisation and sonification of climate data allow for new points of entry and connection within and through the data. Examples of artistic and design practices in this direction abound. One of the interesting examples Gabrys and Yusoff mention is the artist duo Gavin Baily & Tom Corby. Their recent work includes the use of meteorological and geological information about the climate in order to visualize the hidden aspects of environmental sites and landscape and to produce speculative geographies and experimental maps. At the heart of this work is an interest in data, employed as a medium beyond a conventional analytic approach to stress its critical, experiential and affective potential. The Northern Polar Studies is a large-scale screen-based installation, which uses data sets from drifting buoys and satellite measurements of Arctic sea ice. This data, collected since the 1980s, has been used to model the retreat of the Arctic by examining the age and distribution of sea ice. In animating this data, the work reveals phantasmagorical three-dimensional shapes and figures, visualizing the landscape of environmental ruination over an extended time period.

Another earlier example is the project Feral Robots (2005) by the artist and engineer Natalie Jeremijenko, who studied biochemistry, physics, neuroscience and precision engineering. Feral Robots is an open source robotics project designed to enable distributed and co-located teams of lay participants to “upgrade” low-end commercially available toys with chemical sensing equipment. The adapted robots “sniff out” environmental toxins; that is, they follow concentration gradients of toxins sensed by their “dog” noses. Not dissimilar to popular robot wars events, this project involves the release of “packs” of feral robotic dogs that have been designed and modified to be released on sites of community interest, including public parks, school grounds and industrial sites.

The lab inside out

The practices mentioned above develop new forms of public engagement within climate science and politics. Engaging with climate change (beyond science) in multiple ways asks questions of the sites, networks, knowledge and practices of constructing, producing or invoking climate. Most importantly, the urgency of climate change seems to give rise to new formations of practices at the intersections of arts and sciences. As Gabrys and Yusoff conclude: “In comparison to arts-sciences discourse that focuses on how to define these disciplines and demarcate their possible intersections, practices of arts and sciences in relation to climate change shift and relocate in new sites of shared concern— often outside the laboratory or the gallery” (2012, pp. 6-7). To conclude, I would like to mention two examples of these practices being developed outside the laboratory and the gallery, in which the arts-sciences relation is being played out: the transdisciplinary studio and the importance of field research as part of artistic research in relation to climate change.

According to Latour, nowadays we should talk about the “the world-wide lab”. By this he means to say that “since the sciences have expanded so much that they have transformed the whole world into a laboratory, artists have per force become white coats among white coats, namely all of us engaged in the same collective experiments” (Latour, 2004c, p. 30). Climate change unfolds in the world, beyond the confines of any single discipline or sealed laboratory space. The lab no longer operates as the ideal referent or even counter-referent for understanding practice related to climate change. According to Donna Haraway (2008), expanded definitions of collectives, which also include nonhumans, are needed.

One remarkable example of the laboratory turned inside out is the rise of the so-called “transdisciplinary studio” in the art world. International artists such as Tomás Saraceno work together with interdisciplinary teams in laboratory-like studio settings and collaborate structurally with scientific research partners and centres. The former notion of the lab is appropriated and inverted into the model of an “ecology of practices” in which different disciplinary knowledges can be combined in often complex research projects. Saraceno’s oeuvre could be seen as ongoing research, informed by the worlds of art, architecture, natural sciences, astrophysics and engineering. His floating sculptures, community projects and interactive installations propose and explore new, sustainable ways of inhabiting and sensing the environment.

An example of such work is Aerocene (2017-present). Aerocene is an artistic project (and not-for-profit organisation) consisting of a series of air-fuelled sculptures that will fly in the longest, most sustainable journey around the world without the use of fossil fuels. These emission-free floating sculptures, made from silver and transparent Mylar, are designed to travel around the earth without helium, batteries or solar panels. Instead, they glide on wind currents and are kept afloat by solar and infrared radiation. As a researcher, Saraceno has collaborated with meteorologists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the lab of the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) to study the jet stream and determine potential flight paths for his aerosolar inflatables. But the work moves beyond the lab in every possible way, engaging a wider public to build and experiment with their own personal Aerocene Explorer.

The idea that the scope of climate change is not limited to the laboratory also finds its origin in the fact that, next to climate models, the majority of climate science relies on data gathering in the field, often in remote areas. Following the so-called “ethnographic turn in art”, artists and designers have shown an increased interest in researching and representing less presented voices in the global discussion on environmental justice, engaging themselves in field research with local communities and indigenous cultures. Ursula Biemann is an artist, writer and video essayist. Her artistic practice is strongly research-oriented and involves fieldwork in remote locations where she investigates climate change and the ecologies of oil, ice and water. An example of this is Forest Law(2014), a project in which she collaborated with Brazilian architect Paulo Tavares. The project is based on research in the oil-and-mining frontier in the Ecuadorian Amazon—one of the most biodiverse and mineral-rich regions on Earth, currently under pressure from the dramatic expansion of large-scale extraction activities. At the heart of Forest Law is a series of legal cases that bring the forest to court in order to plead for the rights of nature. It tells the story of the indigenous people of Sarayuku who won one of these trials based on their cosmology of the living forest. The project emerges through a process of Biemann and Tavares video-graphing their journey through Amazonia, recording the stories of the people they encounter and collecting diverse kinds of documentation, ultimately resulting in a multimedia art installation and an artist’s book.

Ecologies of practice

The intention of this article is to show how transdisciplinary practices in art and design responding to climate change may indicate the ways in which the field of arts and sciences, with respect to climate change, undergo a transformation, both in their practices and subjects of study. Its intention is also to show how relevant these new intersectional practices are for the future of art and design education. How do we create educational spaces in which students are able to learn how to emotionally and imaginatively respond to wicked problems such as climate change, while basing their experimentation on solid research? What kind of historical heritage or ethical consciousness—of the scale of the problem and its intergenerational nature—do we teach our students? How can we teach them to think and design speculatively? How do we teach them, most importantly perhaps, that creative practice can do more than mediate science and can instead bring into play new approaches to publics, science production and politics? Most of all, the wickedness of a problem like climate change forces us to think in terms of “ecologies of practice” and multiplicity, progressively exploring and transgressing boundaries between artistic and design research and the other “sciences”.

Artist Websites

Pinar Yoldas

http://cargocollective.com/yoldas

Tomás Saraceno, Aerocene

Superflux

Gavin Baily & Tom Corby

Ursula Biemann

https://www.geobodies.org

References

Ardern, J. (2016, April 4). Mitigation of shock journal. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://superflux.in/index.php/mitigation-of-shock-journal/#

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Braidotti, R., & Hlavajova, M. (Eds.). (2018). Posthuman glossary. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Gabrys J., & Yusoff, K. (2011). Climate change and the imagination. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2(4), 516-534.

Gabrys J., & Yusoff, K. (2012). Arts, sciences and climate change: Practices and politics at the threshold. Science as Culture, 21(1), 1-24.

Galafassi, D., Kagan, S., Milkoreit, M., Heras, M., Bilodeau, C., Juarez, S., . . . Tàbara, J.D. (2018). ‘Raising the temperature’: The arts in a warming planet. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 31, 71-79.

Hamilton, C. (2017). Defiant earth: The fate of humans in the Anthropocene. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Haraway, D. (2008). When species meat. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Huygen, M. (2018, 25 March). Zorgen over snelle groei studies met losse vakken [Concern with rapidly growing multidisciplinary studies]. NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved from https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2018/03/25/zorgen-over-snelle-groei-studies-met-losse-vakken-a1597063

Latour, B. (2004a). Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern. Critical Inquiry, 30(2), 225-248.

Latour, B. (2004b). Politics of nature: How to bring the sciences into democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (2004c). Atmosphère, atmosphère. In S. May (Ed.), Olafur Eliasson: The weather project (pp. 29-41). London, UK: Tate Publishing.

Lykke, N. (2018). Postdisciplinarity. In R. Braidotti & M. Hlavajova (Eds.), Posthuman glossary (pp. 332-335). London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sheridan, S. L. (1990). Why new foundations? Leonardo, 23(2-3), 165-167.

Snow, C. P. (1990). The two cultures. Leonardo, 23(2-3), 169-173. (Original work published 1959).

Stengers, I. (2000). The invention of modern science. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stengers, I. (2005). Introductory notes on an ecology of practices. Cultural Studies Review, 11(1), 183-106.

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Yoldas, P. (2016, February 8). What is Speculative Biology? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@pinaryoldas